What's next for the US economy?

As the US economy recovers and post-pandemic spending gets underway, fund managers are reviewing their exposure to US equities

As the US reopens for business, households that were able to save cash during lockdown are beginning to spend it. But this could have repercussions for the economy and challenges are anticipated for businesses and policymakers.

Nevertheless, there is optimism about the ability of the economy to cope with whatever comes next, as some fund managers look to increase their exposure to US equities.

And UK advisers intend to maintain their present level of exposure to equities, despite economic uncertainty and the lingering impact of the pandemic.

So, will the outlook remain largely positive or could post-pandemic difficulties paint a very different picture?

Advisers sticking with equities despite market uncertainty

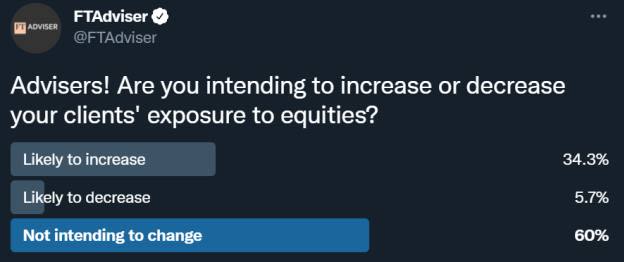

A clear majority of advisers are intending to retain their present level of exposure to equity markets, despite uncertainties around the economic environment and exit from the pandemic, according to the latest FTAdviser poll.

The poll, which was conducted via the FTAdviser Twitter account, found that 60 per cent of respondents intend to keep their present level of equity exposure, while just over a third (34 per cent) intend to increase equity exposure from here.

The poll was coming during a turbulent time in equity markets, with concerns around monetary policy, inflation turning to stagflation, and the prospect of interest rates rising.

In addition, October is traditionally a volatile month in equity markets. But as the month wore on, the volatility has been confined to a small number of sectors seen as particularly vulnerable to policy changes.

The initial market wobble related to the potential collapse of the Chinese property company Evergrande has also faded from the markets' memory.

Investors have been increasingly wary of the outlook for growth equities in areas such as big tech and consumer durables, but there has been some element of recovery in these areas, with, for example, the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust trading at a higher level today (October 25) than it was a month ago.

Among the value equities, the easing of concern around the outlook for Chinese equities has boosted the shares of mining companies.

The outlook for US stocks

Ian Heslop, who runs both global and North American-specific mandates at Jupiter, says the problem facing investors over the past decade has been that, while valuations have been high, if one took a decision to have less US exposure than the index, “you would have been wrong for most of the past decade”.

Heslop has spent most of that time “cautious” on the outlook for the US, saying “there has for the past decade always been a reason not to own US stocks, but it is a market which has ridden the wave of technology-stock outperformance and of quality growth outperformance”.

But he feels the tide is about to turn. He says: “There is quite a strong correlation between the strong performance of technology shares and low interest rates. And it makes sense that such a correlation exists, as technology shares are long-duration assets.”

Long-duration assets are defined in the market as being those that will deliver most of their returns in the future. Heslop feels technology companies fit into this category because their present valuations reflect not just the revenues and profits earned today, but the potential for those to grow in future years.

Higher interest rates are negative for long-duration assets because they increase the returns available from cash and bonds today. By owning a long-duration asset one is sacrificing higher short-term returns for potential returns in future, and the higher rates are, the greater the sacrifice.

Heslop says the level of rotation over the past 12 months between value and growth stocks “is a portent of things to come” in markets.

He says the nature of the present economic climate, with supply-side inflation rising, may impact on the returns from equities in a generally negative way, but that in such a climate he would expect value-based equities to perform better than growth.

Heslop notes: “The type of inflation we have now is not a portent for strong economic growth. But the era of low and stable interest rates is also probably over.”

Andrew Bell, chief executive of the Witan investment trust, says the issue with the big tech companies is that “in many cases 80 per cent of the valuation they trade at now is about earnings that they are expected to make in 15 years. Any change in inflation and interest rates is going to impact on those valuations. Some of the tech companies may actually be very good investments on a 10-year view, but in the shorter term, the level of certainty around these valuations has been reduced. For the very highest-valued stocks, people are going to work harder at assessing them in a world of higher inflation”.

Heslop notes that a combination of strong business performance and relatively poor share-price performance means the largest technology companies now trade at multiples that are closer to 20 times earnings than 30 times, but he feels this valuation level is still sufficiently high that it will lead to relative underperformance against the value stocks.

The type of inflation we have now is not a portent for strong economic growth

The reason the US equity market may be particularly vulnerable to a shift in market sentiment away from growth stocks is that it is the market that has more of those than any other developed market. If value comes into favour, then those markets that have more relative exposure to value stocks – notably the UK and Europe – may outperform.

But the challenge to this narrative, as acknowledged by Heslop, is that many value stocks do well when economic growth is strong, and that may not be the case.

Bell says the present supply-side issues globally are “like bugs on the windscreen”, rather than longer-term concerns, and he expects economic growth to be robust.

Kevin Thozet, a member of the investment committee at Carmignac, is of the view that the present bout of global inflation could be longer lasting than many market participants anticipate, and says this may mean economic growth is lower next year than this.

But he says in such a scenario, it should not be taken for granted that commodities will do well, as the outlook for that asset class is uncertain in a world where sustainability is of increasing relevance.

He adds that much of the growth in the valuations of large tech stocks is the result of those companies performing well, and so does not feel that a change in monetary conditions will have a long-term negative impact on the share prices of those assets.

James Thomson, who runs the £3.9bn Rathbone Global Opportunities fund, has responded to the uncertainty by increasing his fund’s US exposure, as he believes the US economy is well-placed to deal with what comes next.

He says: “We have recently taken our US exposure close to an all-time high. We believe the US can withstand the oil and inflationary shocks, given the S&P 500’s lower relative exposure to goods-producing sectors and the American economy’s declining energy intensity.

"Most US households have an incredible savings buffer, with cumulative excess savings coming out of the pandemic and lower debt balances.

"Higher inflation is likely to hurt lower-income people and students the most as rent, gas and goods represent a larger share of their wallet."

He adds: "While the acceleration in overall inflation did clip consumer spending in the third quarter, we think the medium-term impact is being overplayed.

"For example, energy now accounts for just 3 per cent of household consumption, therefore the impact of oil-price spikes will be smaller than it has been in the past.

"Sadly, the inflationary spike – or even just product availability – will hit smaller businesses most harshly, while those with scale and buying power should be able to absorb the cost or put up prices more modestly to maintain price leadership and gain market share."

Cormac Weldon, who manages £2.7bn across two US equity funds at Artemis, says there are reasons to be pessimistic on US equities, but only at the margin.

He says: “We are a bit less optimistic than we were about the US a few months ago, but not drastically so. On the plus side, we still have a huge savings rate in the US. People have a lot of money that they saved through Covid that we think will support demand through the back of the year and into next year.

Higher inflation is likely to hurt lower-income people and students the most

"We expect people to start travelling again much more in the next six to nine months, though that is a little offset by rising gasoline prices. You have to remember that a hike in petrol has a bigger relative impact at the pump for Americans than it does in the UK. Here we pay nearly 60p a litre in tax on petrol, which means when the price of petrol goes up it moves the price at the pump less, relatively speaking. We’ve seen a rise from £1.15 to £1.35 – an increase of 17 percent – in the past year in the UK.

"In the US, where they think in gallons but pay in cents, prices have gone from $2.18 to $3.30 in a year – a rise of 50 per cent. That has an impact on consumers. We are also having to factor in the expectation that inflation is going to be higher for longer.

"And Covid hasn’t gone away. After a good start, the US vaccination rate has plateaued and isn't as high as it is in other developed countries. That creates a bit of uncertainty, but I don’t think it will be a huge factor. “

Richard De Lisle, manager of the VT De Lisle US fund, says it is not inevitable that stagflation happens in the US, as the Biden government is embarking on a programme of substantial infrastructure spending, which should boost domestic economic growth.

He expects this to lead to inflation but also to boost economic growth, and advocates investing in commodities and some of the smaller banks as protection from inflation.

De Lisle notes that in the 1970s – a period of very high inflation in the US – it was not the established larger companies on the stock market that performed best, despite the perception that those businesses would have pricing power.

He says: “The US is about 59 per cent of the global market, but under Biden the time has come to look at a broader range of US shares than has been the case for the past decade.”

Felix Wintle, who runs the US equity mandate at Tyndall, says: “I don't think it’s wise to make big, long-term predictions on what the outlook for inflation will be. But economic cycles have not disappeared so maybe people will have to think differently about what will work in the next stage of the cycle. I think we are going to have higher inflation in the months ahead.”

Gabrielle Boyle, global equity fund manager at Troy, says the rise of technological adoption is itself deflationary, and this may mean inflation does not get out of control, but she believes "that there are companies listed in the US which can perform well in either environment", and cites credit card companies as an example.

She says these have not traded at the very high valuations associated with technology businesses, but are also growing as people buy more online and also do not care if inflation rises or not because the fee they get from each transaction is small – "and there are lots of quality companies like that in the US, so you don’t have to make macro predictions, which are very difficult to get right".

Eren Osman, co-chief investment officer at Arbuthnot Latham, says he expects commodity price inflation to become a longer-term trend, but also expects technology companies to perform well.

The US has the greatest collection of high-quality companies

When choosing funds for exposure to the US, he says he prefers to invest with managers that own only a relatively small number of equities in their funds, “as the academic research shows that most fund manager outperformance comes from a small number of holdings, while a large number contribute nothing or are negative. The tech companies are not going to vanish; the long-duration asset label underplays the fact these technology companies are growing their earnings and the opportunity they have to keep growing their earnings in future”.

George Dent, a fund manager at Edinburgh-based Walter Scott, says that while the US market looks expensive relative to other developed markets, “none of those markets look cheap, but the US probably deserves to trade at a bit of a premium to the rest because it has the greatest collection of high-quality companies”.

Will Hobbs, chief investment officer at Barclays Wealth, says the returns from an individual country or investment style are acutely difficult to predict, but that at a time when valuations are generally high, it might be that the best opportunities are to be found in the “less-fished parts of the market”, and that points away from US large-cap stocks right now, as so many clients have very substantial exposure there.

He believes that one outcome of the technological change that is sweeping the world is that big brands will be less powerful in the digital age.

David Thorpe is special projects editor at FTAdviser

‘Boom and bust’ for the US consumer?

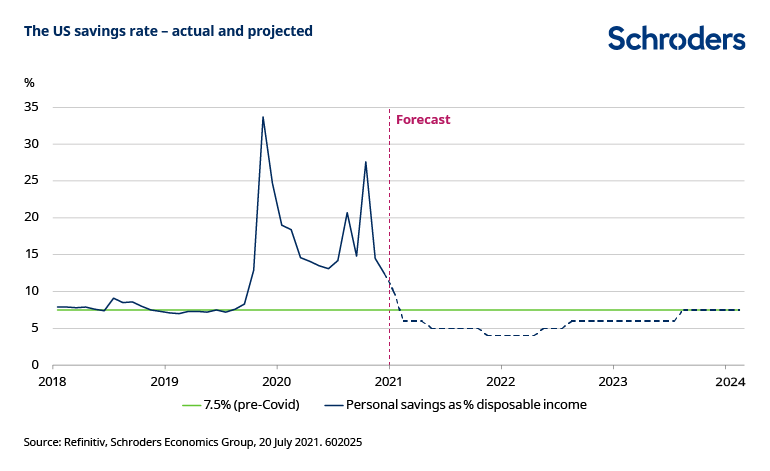

As the US economy reopens one of the key drivers of the recovery is expected to be the release of this pent-up demand from households. An estimated $2.3tn (£1.6tn) has built up since the pandemic hit the US last year, equivalent to around 13 per cent of household disposable income.

Not all of this will be spent as households will leave some in bank accounts, pay down debt or add to their investments. Nonetheless, there should be a substantial boost to consumption, which, as the largest component of national income, should help take GDP growth over 6.5 per cent this year.

On the basis of surveys and our own analysis we estimate that households will spend around 40 per cent of their excess savings over the next two to three years. Such an assumption is in line with surveys such as those by YouGov, which suggest 46 per cent intend to spend some of their extra savings and 26 per cent wish to consume half or more of it.

While welcome for the economy and jobs, the release of pent-up demand has the potential to create a ‘boom and bust’ scenario for the consumer and the economy.

Our forecasts are based on the view that households will run down a significant part of their excess savings and then return to the rate of savings seen before the pandemic. That would imply a period where the savings rate falls sharply over the next year and then builds back up again. This has the effect of first driving consumption strongly, before leading to a period of weakness. For example, we could see real consumption growth of 7 per cent this year, followed by only 1.5 per cent in 2022.

The pattern is somewhat exacerbated by fiscal policy as tax cuts and enhanced benefits have boosted household incomes in 2020 and Q1 this year.

Spending took a big jump up in March as president Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan came through. Going forward though, the US consumer faces something of a fiscal cliff as benefits are withdrawn. Further stimulus is coming, but at this point will be more focused on investment and infrastructure than payments to households.

Hangover to follow the binge

On this view we see an outlook where initially the run down of excess savings will help cushion consumer spending as benefits fade. As this too runs its course, however, consumer spending should cool significantly in 2022.

Of course, there is considerable uncertainty over this outlook. Our analysis assumes that excess savings have built up evenly across the income spectrum, whereas we know that higher income households (frequently working from home in well-paid service sector roles) have tended to gain more. The marginal propensity to consume of this group tends to be lower than average and so would tend to temper the fluctuations in consumption. Many could just permanently add their excess savings to their existing wealth.

More immediately, a potential boom could be stifled by higher inflation. The service sector is struggling to reopen quickly enough to meet the increase in demand as hotels, restaurants and others report shortages of labour and difficulty restarting. The latest CPI inflation numbers saw significant jumps in prices in these reopening sectors as businesses responded to excess demand.

Meanwhile, the manufacturing sector, which has largely continued to operate at high capacity (helped by online sales), has hit shortages of key components such as semi-conductor chips. It is also having to pay more for commodities and transportation. This is leading to bottlenecks, higher prices and waiting lists for products, delaying stronger expenditure.

Surveys of consumers, such as those conducted by the University of Michigan, show that higher inflation is adversely impacting confidence and will reduce real disposable income and spending.

Finally, travel restrictions may limit the pick-up in spending. It seems likely that many will want to use their excess savings on a holiday but are limited by ongoing restrictions, particularly for international travel. This element of pent-up demand may not be realised for some time given the spread of the delta variant.

Overall though, given the scale of excess savings/pent-up demand, it seems likely that we will see significant fluctuations in consumer spending driven by shifts in the savings rate. Our central assumption that less than half the excess savings finds its way into consumption still generates considerable volatility in spending.

Such volatility is unusual as for most of the past decade consumption has moved in line with gradual changes in real incomes with fluctuations in the savings rate playing only a minor role. However, the household sector will be looking to return savings toward equilibrium, or a more normal level and make up for lost time during the pandemic. This year could be the strongest year since 1973 for consumer spending, followed by one of the weakest.

All of which makes for a challenging outlook for business and policymakers. Businesses will have to take a view on whether the increase in demand is temporary or permanent and whether to adjust prices or add capacity. Central banks will have to decide whether to lean into the initial boom and tighten monetary policy, or wait for a slowdown.

If such key actors misjudge the sustainability of demand, such an environment creates the risk of over-production or over-tightening and will only exacerbate the economic cycle.

Keith Wade is chief economist and strategist at Schroders